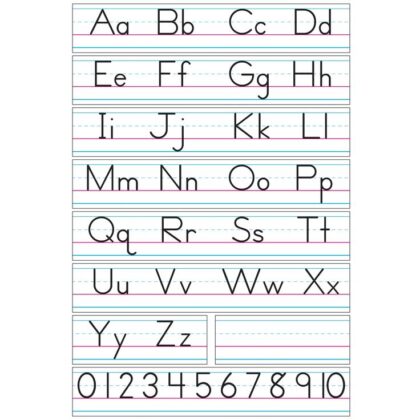

I received a note from someone recently on penmanship paper. You may have used this distinctive lined paper in school. Apparently, it’s been in use for more than a century. It has a solid blue horizontal line indicating the upper boundary of letters, a solid red line indicating the proper base for letters, and a dotted line halfway in between. Sometimes, it’s called handwriting practice paper.

It’s been a long time since I used this kind of paper. But when I was first learning to write, I imagine it was very useful. Now I can write things pretty quickly without concentrating on how the letters look. When I was first starting out, though, I needed a frame of reference for the boundaries of various letters. And without a clear foundation line, I might have wandered all over the page, which makes things unclear for a potential reader.

A few months back, in Sunday morning worship, we explored a mental framework called the Immunity to Change Map. We haven’t talked about it much sense then, and maybe you haven’t given it a lot of thought. But seeing the note on penmanship paper reminded me how useful it is to have a framework when I’m working on learning new behavior.

You might recall that the Immunity Map has four different sections. The first is a clearly defined commitment. Maybe for us as a community, that commitment is to create safe space for people to connect authentically and deeply. Or maybe a congregational commitment in this moment is to ensure that our physical space fits our ministries, and to care for that physical space well.

Whatever it is, we often engage in a bit of self-sabotage when it comes to big commitments. That’s the second column of the Map. What do we do instead of honoring that big commitment? How do we avoid being “all in” with that commitment? And then, the third column is about why. What are our competing commitments?

Maybe we fear rejection, so we stick with relationships we already have rather than reach out to people we don’t know yet. Maybe we focus on smaller, less impactful decisions because caring for our entire physical space feels overwhelming. It could be anything. And it’s usually a lot of different things.

The fourth and final column is for naming the assumptions underneath our competing commitments. Like the assumption that we’re going to be rejected by someone. And that assumption may be built on an assumption that we aren’t acceptable or worthy just as we are.

When we name our assumptions (or write them down clearly), we often become aware of how obviously untrue those assumptions are. Or we become aware of a growth edge for focused spiritual work. And in doing this, we open space to commit more deeply to the big vision we identified way back in that first column, without our competing commitments and fears getting in the way.

It’s kind of like using penmanship paper. We start with a framework that lets us define the boundaries of what we want to create—clear guidelines that also help us notice when we veer away from that vision. And over time, if we use that framework well, we eventually need those guide-lines less and less. We become more competent at living into a big vision.

And like everything else we do, we’re fortunate to have companions along on the journey, co-creating and holding up mirrors and sharing in the big vision we have for what our community can be. It’s almost like we’re penmanship paper for one another. And our values and covenant are penmanship paper for all of us together.

Share this post: